Lignin-Containing Cellulose Nanomaterials: A Promising New Nanomaterial for Numerous Applications

-

Abstract: The demand for sustainable functional materials with an eco-friendly preparation process is on the rise. Lignocellulosics has been attributed as the most sustainable bioresource on earth which can meet the stringent requirements of functionalization. However, cellulose nanomaterials obtained from lignocellulosics which has reached advanced stages as a sustainable functional material is challenged by its preparation procedures. These procedures can not best be described as sustainable and eco-friendly owning to lots of energy and chemicals spent in the pre-treatment and purification processes. These processes are intended to aid fractionation into the major components in order to remove lignin and hemicellulose for the production of cellulose nanomaterials. This work is thus centred on reviewing the progress achieved in introducing a new cellulose nanomaterial containing lignin. The preparation processes, properties and applications of this new lignin-containing cellulose nanomaterial will be discussed in order to chart a sustainable preparation route for cellulose nanomaterials.

-

Key words:

- lignocellulose nanofibers /

- pre-treatment /

- bioresources /

- lignin /

- biomass /

- nanocellulose

-

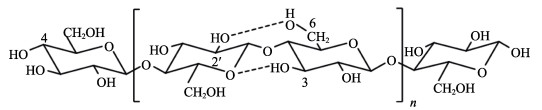

Figure 2. Basic lignin structure showing its bonds and linkages (Jiang and Hu, 2016)

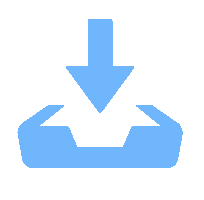

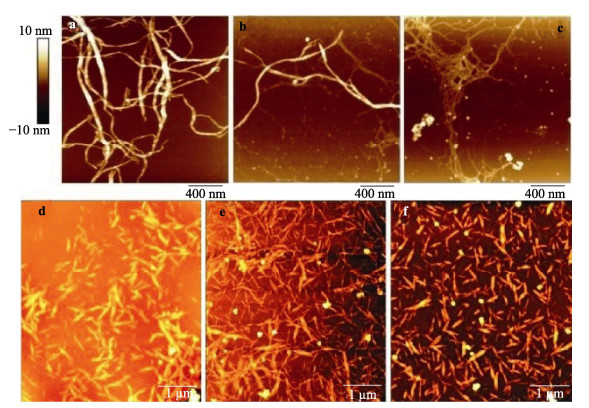

Figure 3. The AFM micrographs of cellulose nanofibers (CNFs) (a), lignin-containing cellulose nanofibers (LCNFs) (b, c) containing 1.7wt% and 3.7wt% of lignin respectively (Rojo et al., 2015), lignin-containing cellulose nanocrystals (LCNCs) (d–f) produced with maleic acid hydrolysis at various reaction time of 30, 60 and 90 min respectively (Bian et al., 2017a)

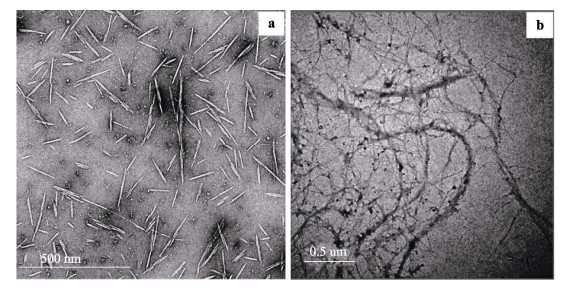

Figure 4. The TEM images of aspen wood LCNCs (a) (Wei et al., 2018) and bamboo LCNFs (b) (Lu et al., 2018)

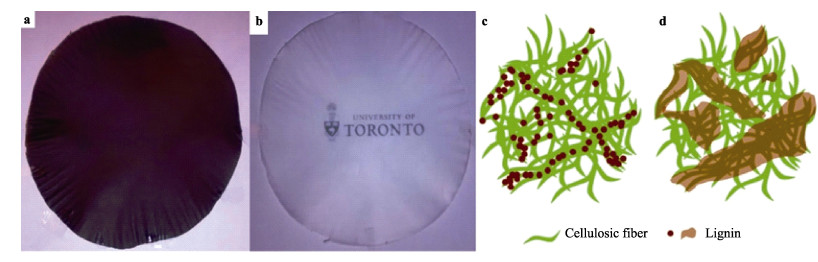

Figure 5. Films made from LCNFs having 23wt% lignin content (a) and CNFs having < 1wt% lignin content (b) (Nair et al., 2017). Model of lignin within nanofibril suspension (c) and nanopapers (d) (Rojo et al., 2015)

-

Abdul Khalil H P S, Davoudpour Y, Islam M N, et al., 2014. Production and modification of nanofibrillated cellulose using various mechanical processes: A review. Carbohydrate Polymers, 99: 649–665. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.08.069. Abe K, Nakatsubo F, Yano H, 2009. High-strength nanocomposite based on fibrillated chemi-thermomechanical pulp. Composites Science and Technology, 69(14): 2434–2437. DOI: 10.1016/j.compscitech.2009.06.015. Arsene M A, Bilba K, Savastano Junior H, et al., 2013. Treatments of non-wood plant fibres used as reinforcement in composite materials. Materials Research, 16(4): 903–923. DOI: 10.1590/s1516-14392013005000084. Bian H Y, Chen L H, Dai H Q, et al., 2017a. Effect of fiber drying on properties of lignin containing cellulose nanocrystals and nanofibrils produced through maleic acid hydrolysis. Cellulose, 24(10): 4205–4216. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-017-1430-7. Bian H Y, Chen L H, Dai H Q, et al., 2017b. Integrated production of lignin containing cellulose nanocrystals (LCNC) and nanofibrils (LCNF) using an easily recyclable Di-carboxylic acid. Carbohydrate Polymers, 167: 167–176. DOI: 10.1016/ j.carbpol.2017.03.050. Brinchi L, Cotana F, Fortunati E, et al., 2013. Production of nanocrystalline cellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: technology and applications. Carbohydrate Polymers, 94(1): 154–169. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.01.033. Brodin M, Vallejos M, Opedal M T, et al., 2017. Lignocellulosics as sustainable resources for production of bioplastics—A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 162: 646–664. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.05.209. Chaker A, Alila S, Mutjé P, et al., 2013. Key role of the hemicellulose content and the cell morphology on the nanofibrillation effectiveness of cellulose pulps. Cellulose, 20(6): 2863–2875. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-013-0036-y. Chen H, 2014. Biotechnology of lignocellulose: theory and practice. Beijing and Springer: Chemical Industry Press. Chen L H, Wang Q Q, Hirth K, et al., 2015. Tailoring the yield and characteristics of wood cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) using concentrated acid hydrolysis. Cellulose, 22(3): 1753– 1762. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-015-0615-1. Chen W S, Yu H P, Liu Y X, et al., 2011. Individualization of cellulose nanofibers from wood using high-intensity ultrasonication combined with chemical pretreatments. Carbohydrate Polymers, 83(4): 1804–1811. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol. 2010.10.040. Diop C I K, Tajvidi M, Bilodeau M A, et al., 2017. Evaluation of the incorporation of lignocellulose nanofibrils as sustainable adhesive replacement in medium density fiberboards. Industrial Crops and Products, 109: 27–36. DOI: 10.1016/ j.indcrop.2017.08.004. Dong S P, Bortner M J, Roman M, 2016. Analysis of the sulfuric acid hydrolysis of wood pulp for cellulose nanocrystal production: A central composite design study. Industrial Crops and Products, 93: 76–87. DOI: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.01.048. Dungani R, Karina M, Subyakto, et al., 2016. Agricultural waste fibers towards sustainability and advanced utilization: a review. Asian Journal of Plant Sciences, 15(1): 42–55. DOI: 10.3923/ajps.2016.42.55. Espinosa E, Sánchez R, González Z, et al., 2017. Rapidly growing vegetables as new sources for lignocellulose nanofibre isolation: Physicochemical, thermal and rheological characterisation. Carbohydrate Polymers, 175: 27–37. DOI: 10.1016/ j.carbpol.2017.07.055. Fukuzumi H, Saito T, Iwata T, et al., 2009. Transparent and high gas barrier films of cellulose nanofibers prepared by TEMPO-mediated oxidation. Biomacromolecules, 10(1): 162–165. DOI: 10.1021/bm801065u. Fukuzumi H, Saito T, Okita Y, et al., 2010. Thermal stabilization of TEMPO-oxidized cellulose. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 95(9): 1502–1508. DOI: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab. 2010.06.015. Grishkewich N, Mohammed N, Tang J T, et al., 2017. Recent advances in the application of cellulose nanocrystals. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science, 29: 32–45. DOI: 10.1016/j.cocis.2017.01.005. Habibi Y, 2014. Key advances in the chemical modification of nanocelluloses. Chemical Society Reviews, 43(5): 1519–542. DOI: 10.1039/c3cs60204d. Han J S, Rowell J S, 1996. Chemical composition of fibers, in paper and composites from agro-based resources. London: CRC Press, 83–134. Henriksson M, Henriksson G, Berglund L A, et al., 2007. An environmentally friendly method for enzyme-assisted preparation of microfibrillated cellulose (MFC) nanofibers. European Polymer Journal, 43(8): 3434–3441. DOI: 10.1016/ j.eurpolymj.2007.05.038. Herrera M, Thitiwutthisakul K, Yang X, et al., 2018. Preparation and evaluation of high-lignin content cellulose nanofibrils from eucalyptus pulp. Cellulose, 25(5): 3121–3133. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-018-1764-9. Huang P, Wu M, Kuga S, et al., 2012. One-step dispersion of cellulose nanofibers by mechanochemical esterification in an organic solvent. ChemSusChem, 5: 2319–2322. DOI: 10. 1002/cssc.201200492. Ioelovich M, 2012. Optimal conditions for isolation of nanocrystalline cellulose particles. Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, 2(2): 9–13. DOI: 10.5923/j.nn.20120202.03. Jiang F, Hsieh Y L, 2013. Chemically and mechanically isolated nanocellulose and their self-assembled structures. Carbohydrate Polymers, 95(1): 32–40. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013. 02.022. Jiang Z C, Hu C W, 2016. Selective extraction and conversion of lignin in actual biomass to monophenols: a review. Journal of Energy Chemistry, 25(6): 947–956. DOI: 10.1016/j.jechem. 2016.10.008. Julkapli N M, Bagheri S, 2017. Progress on nanocrystalline cellulose biocomposites. Reactive and Functional Polymers, 112: 9–21. DOI: 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2016.12.013. Kalia S, Kaith B S, Kaur I, 2011. Cellulose fibers: bio- and nano-polymer composites. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. Li Y N, Liu Y Z, Chen W S, et al., 2016. Facile extraction of cellulose nanocrystals from wood using ethanol and peroxide solvothermal pretreatment followed by ultrasonic nanofibrillation. Green Chemistry, 18(4): 1010–1018. DOI: 10.1039/c5gc02576a. Lorenz M, Sattler S, Reza M, et al., 2017. Cellulose nanocrystals by acid vapour: towards more effortless isolation of cellulose nanocrystals. Faraday Discussions, 202: 315–330. DOI: 10.1039/c7fd00053g. Lu H L, Zhang L L, Liu C C, et al., 2018. A novel method to prepare lignocellulose nanofibrils directly from bamboo chips. Cellulose, 25(12): 7043–7051. DOI: 10.1007/ s10570-018-2067-x. Mohamad Haafiz M K, Eichhorn S J, Hassan A, et al., 2013. Isolation and characterization of microcrystalline cellulose from oil palm biomass residue. Carbohydrate Polymers, 93(2): 628–634. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.01.035. Mondal S, 2017. Preparation, properties and applications of nanocellulosic materials. Carbohydrate Polymers, 163: 301–316. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.12.050. Morales L O, Iakovlev M, Martin-Sampedro R, et al., 2014. Effects of residual lignin and heteropolysaccharides on the bioconversion of softwood lignocellulose nanofibrils obtained by SO2-ethanol-water fractionation. Bioresource Technology, 161: 55–62. DOI: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.03.025. Nair S S, Kuo P Y, Chen H Y, et al., 2017. Investigating the effect of lignin on the mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of cellulose nanofibril reinforced epoxy composite. Industrial Crops and Products, 100: 208–217. DOI: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.02.032. Nair S S, Yan N, 2015. Effect of high residual lignin on the thermal stability of nanofibrils and its enhanced mechanical performance in aqueous environments. Cellulose, 22(5): 3137–3150. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-015-0737-5. Nechyporchuk O, Belgacem M N, Bras J, 2016. Production of cellulose nanofibrils: a review of recent advances. Industrial Crops and Products, 93: 2–25. DOI: 10.1016/j.indcrop. 2016.02.016. Pääkkö M, Ankerfors M, Kosonen H, et al., 2007. Enzymatic hydrolysis combined with mechanical shearing and high- pressure homogenization for nanoscale cellulose fibrils and strong gels. Biomacromolecules, 8(6): 1934–1941. DOI: 10.1021/bm061215p. Pejic B M, Kostic M M, Skundric P D, et al., 2008. The effects of hemicelluloses and lignin removal on water uptake behavior of hemp fibers. Bioresource Technology, 99(15): 7152–7159. DOI: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.12.073. Peng S, Xu Q, Fan L L, et al., 2016. Flexible polypyrrole/cobalt sulfide/bacterial cellulose composite membranes for supercapacitor application. Synthetic Metals, 222: 285–292. DOI: 10.1016/j.synthmet.2016.11.002. Phanthong P, Reubroycharoen P, Hao X G, et al., 2018. Nanocellulose: extraction and application. Carbon Resources Conversion, 1(1): 32–43. DOI: 10.1016/j.crcon.2018.05.004. Poletto M, Zattera A J, Forte M M C, et al., 2012a. Thermal decomposition of wood: influence of wood components and cellulose crystallite size. Bioresource Technology, 109: 148–153. DOI: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.11.122. Poletto M, Zattera A J, Santana R M C, 2012b. Thermal decomposition of wood: Kinetics and degradation mechanisms. Bioresource Technology, 126: 7–12. DOI: 10.1016/j.biortech. 2012.08.133. Rojo E, Peresin M S, Sampson W W, et al., 2015. Comprehensive elucidation zof the effect of residual lignin on the physical, barrier, mechanical and surface properties of nanocellulose films. Green Chemistry, 17(3): 1853–1866. DOI: 10.1039/c4gc02398f. Sabo R, Yermakov A, Law C T, et al., 2016. Nanocellulose-enabled electronics, energy harvesting devices, smart materials and sensors: a review. Journal of Renewable Materials, 4(5): 297–312. DOI: 10.7569/jrm.2016.634114. Salas C, Nypelö T, Rodriguez-Abreu C, et al., 2014. Nanocellulose properties and applications in colloids and interfaces. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science, 19(5): 383–396. DOI: 10.1016/j.cocis.2014.10.003. Sánchez R, Espinosa E, Domínguez-Robles J, et al., 2016. Isolation and characterization of lignocellulose nanofibers from different wheat straw pulps. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 92: 1025–1033. DOI: 10.1016/ j.ijbiomac.2016.08.019. Sharma P R, Varma A J, 2014a. Functionalized celluloses and their nanoparticles: morphology, thermal properties, and solubility studies. Carbohydrate Polymers, 104: 135–142. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.01.015. Sharma P R, Varma A J, 2014b. Thermal stability of cellulose and their nanoparticles: effect of incremental increases in carboxyl and aldehyde groups. Carbohydrate Polymers, 114: 339–343. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.08.032. Spence K L, Venditti R A, Rojas O J, et al., 2011. A comparative study of energy consumption and physical properties of microfibrillated cellulose produced by different processing methods. Cellulose, 18(4): 1097–1111. DOI: 10.1007/s10570- 011-9533-z. Stark N M, 2016. Opportunities for cellulose nanomaterials in packaging films: a review and future trends. Journal of Renewable Materials, 4(5): 313–326. DOI: 10.7569/jrm.2016. 634115. Tarrés Q, Ehman N V, Vallejos M E, et al., 2017. Lignocellulosic nanofibers from triticale straw: the influence of hemicelluloses and lignin in their production and properties. Carbohydrate Polymers, 163: 20–27. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol. 2017.01.017. Thomas S, Paul S A, Pothan L A, et al., 2011. Natural fibres: structure, properties and applications//Thomas S, Paul S A, Pothan L A, et al. Cellulose fibers: bio- and nano- polymer composites. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2011: 3–42. Trache D, Hussin M H, Haafiz M K M, et al., 2017. Recent progress in cellulose nanocrystals: sources and production. Nanoscale, 9(5): 1763–1786. DOI: 10.1039/c6nr09494e. Wang X D, Yao C H, Wang F, et al., 2018. Cellulose-based nanomaterials for energy applications. Small, 14(10): 1704152. DOI: 10.1002/smll.201704152. Wei L Q, Agarwal U P, Matuana L, et al., 2018. Performance of high lignin content cellulose nanocrystals in poly(lactic acid). Polymer, 135: 305–31z3. DOI: 10.1016/j.polymer.2017.12.039. -

下载:

下载:

WeChat: JournalBandB

WeChat: JournalBandB