| Citation: | Quan Zhou, Zijing Zhao, Litao Wang, Jiandong Wang, Lina Fu, Jihong Cui, Guosheng Liu, Jie Yang, Yujie Fu. Immobilized enzyme microreactor system with bamboo-based cellulose nanofibers for efficient biotransformation of phytochemicals[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2025, 10(2): 224-238. doi: 10.1016/j.jobab.2025.03.004 |

As the most abundant carbon-neutral resource, lignocellulose biomass is applied in fields such as wastewater remediation, energy production, and functional material preparation (Tripathi et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024). Bamboo stands out as a promising cellulose fibers source due to its rapid growth, high cellulose content, large aspect ratio, and remarkable mechanical properties (Wang et al., 2014). However, the application of bamboo fibers has always been overlooked, most of them will rot or accumulate for incineration, not only causing waste of resources, but also causing environmental pollution problems (Guo et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2025). Compared with other biomass materials, bamboo stands out as a highly promising source of cellulose fibers. Bamboo has the characteristics of high cellulose content, low density, large aspect ratio, and excellent mechanical properties (Misnon et al., 2014; Prakash and Ramakrishnan, 2014; Thakur et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014; Yan et al., 2014; Devireddy and Biswas, 2016; Jatti et al., 2016). And compared to wood fibers, bamboo fibers have advantages such as antibacterial properties and higher sustainability (Mai et al., 2022).

Cellulose nanofibers (CNFs) exhibit unique nanostructural advantages characterized by biocompatibility, environmentally degradable properties, and surface modification capabilities (Zhang et al., 2022). The nanoscale size and high specific surface area of CNFs can enhance the capacity for enzyme immobilization, thereby optimizing the performance of enzymatic systems (Du and Feng, 2023). The oxidation process converts the hydroxyl groups of cellulose into carboxyl groups, introducing stable negative charges on the surface of cellulose. During oxidation, the hydroxyl groups in cellulose can be converted into negatively charged carboxyl groups (Saito et al., 2007). The CNFs can be made by physically and chemically treating plant fibers removing lignin, which allows the distinct layers of the cell wall to integrate and establish three-dimensional microfiber networks in the bamboo fiber (Chen et al., 2020). Therefore, preparing CNFs using bamboo as raw material has efficient loading performance and potential in constructing enzyme-loaded microreactors.

The methods for preparing CNFs by oxidizing cellulose raw materials include 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpipridinoxy (TEMPO) oxidation, deep eutectic solvents (DESs) oxidation, and ammonium persulphate (APS) oxidation. The CNFs prepared by TEMPO oxidation method carry high-density negative charges on the surface. However, the NaClO oxidant used in the oxidation process is highly toxic due to thermal decomposition, which causes significant environmental pollution with chlorine gas (Xu et al., 2023). The DESs oxidation method has a low preparation cost, but generally requires coordination with microfluidization methods to obtain high yields of CNFs (Sirviö et al., 2019). The APS oxidation method uses APS as an oxidant to directly prepare highly carboxylated CNFs from cellulose raw materials while removing non-cellulosic constituents (Chen et al., 2023). The crystallinity of cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) extracted directly from fiberboard fibers using APS increased from 42.5% to 62.7% (Khanjanzadeh and Park, 2021). The crystallinity of CNCs obtained from corncob waste residue by APS oxidation method reached 52.3%, and the carboxyl content reached 0.59 mmol/g, indicating a high degree of oxidation (Zeng et al., 2024). Therefore, APS is a potential alternative to other oxidants as it can directly extract CNFs from biomass and preserve the cellulose structure well, and highly carboxylated CNFs are more conducive to the binding of enzymes to cellulose.

Immobilization techniques are usually categorized by interaction mechanisms into two categories: chemical and physical (Balakrishnan et al., 2024). Chemical immobilization relies on the formation of strong bonds between the enzyme and the carrier, such as covalent and ionic bonds, which enhances the anchoring of the enzyme and the carrier, but conformational changes in the enzyme may lead to denaturation and low activity. Physical immobilization includes adsorption, ionic bonding, entrapment and encapsulation (Prabhakar et al., 2025). Among them, as a mild method for immobilizing enzyme, physical adsorption can prevent the active center of enzyme from being easily damaged and effectively maintain enzyme activity (Li et al., 2024).

Compared to traditional free enzyme, immobilized enzyme has more advantages in certain bioreactors. Firstly, immobilization can enhance enzyme activity by providing a favorable microenvironment. For example, due to the ionic surface and covalent binding of enzyme on the carrier, the enzyme immobilized on the magnetic ion carriers was exhibited higher activity than free enzyme over a wide temperature range (Hosseini et al., 2018). Secondly, immobilization can provide an environment that protects enzymes from degradation and denaturation, thereby enhancing their thermal and operational stability. In addition, the reusability of immobilized enzyme plays a role in reducing the cost of enzymatic hydrolysis in industrial applications. Free enzymes can be separated and reused with devices like ultrafiltration membranes, but it may cause loss of enzyme activity and filter blockage (Jiang et al., 2024). Immobilization enzyme is easy to separate from reaction mixtures and retain high residual activity after multiple uses. The lipase immobilized on a magnetic graphene oxide carrier still exhibited 76.5% residual activity after eight repeated hydrolysis of p-nitrophenol palmitate (Hou et al., 2024b).

The immobilized enzyme technology has great potential in biotransformation. For example, magnetite nanoparticles and dopamine functionalized cellulose nanocrystals were used for high-performance biomass biotransformation with a 20%–76% increase in yield (Ariaeenejad et al., 2021). Dopamine, hydrogen peroxide, and copper sulfate co-deposited with recyclable vanillin to immobilize laccase, increasing the conversion rate of lignocellulose to 88.1% (Lin et al., 2023). The integrating enzymes immobilized in a covalent organic framework converted inulin into D-alloulose, and maintained an initial catalytic efficiency of over 90% after continuous reaction for 7 d (Zheng et al., 2024). Therefore, screening and designing enzyme immobilization carriers are paramount for efficient enzymatic microreactors.

Microreactor technology utilizes nanobiocatalysts to expand the available surface area and/or retain enzyme molecules within the microreactor for continuous use (Gkantzou et al., 2021). Immobilized enzyme microreactors have been widely used in biotransformation due to their notable specific surface area advantages and high mass transfer efficiency (Meng et al., 2018; Balakrishnan et al., 2024). The dopamine and polyethyleneimine co-deposited loading cellulase microreactor can effectively hydrolyze carboxymethyl cellulose and produce sugars, producing a glucose yield that surpasses other reaction systems by 97.2% (Lin et al., 2022). There are also studies exploring the application of free laccase in a microreactor to catalyze the oxidation of catechol, resulting in an 18–167-fold increase in oxidation rate compared to large reactors (Tušek et al., 2013). However, nanomaterials can be used for the preparation of enzyme microreactors due to their large surface area and low mass transfer resistance (Ariaeenejad et al., 2019). Therefore, selecting suitable nanomaterials as immobilized enzyme carriers is crucial. The current nanocarriers used for enzyme immobilization mainly include nanoparticles, nanofibers, nanotubes, nanosheets, and nanocomposite scaffolds. After immobilizing β-galactosidase on amino and trichloro modified silica nanoparticles, 72% of the initial activity was still retained under high-temperature incubation (Banjanac et al., 2016). But there are some metal nanoparticles that can affect the conformation of enzymes, thereby affecting the operational stability of immobilized enzyme. Nanocellulose is used as a carrier to covalently immobilize laccase. Compared with free laccase, this immobilized enzyme exhibits excellent thermal and pH stability, and can maintain 85% of its initial enzyme activity even after being reused five times in the degradation of simulated dye wastewater (Sathishkumar et al., 2014). However, the high stability of nanocellulose water suspension makes it difficult to separate it from the reaction system using high-speed centrifugation and other methods. The Fe3O4 nanoparticles have excellent binding capacity, high fixation efficiency, and can be easily separated from the reaction medium using external magnets, thereby improving their reusability (Gennari et al., 2020). This study combines bamboo nanocellulose with Fe3O4, which not only possesses the relevant characteristics of nanocellulose, but also provides the possibility of adding multiple functional groups through chemical modification to immobilize enzyme.

Genipin, a plant compound with low toxicity, good biocompatibility and a high capacity for crosslinking (Liu et al., 2022), is widely distributed across various plant species. Genipin can interact with various biomolecules such as protein, collagen, gelatin, and chitosan, enabling the development of biological materials like wound dressings, artificial bones, and extracellular matrices (Li et al., 2015). However, the production technology for high-purity genipin in China is not yet mature enough, and there are few commercially available products to choose, which greatly limits the scope of use and research and development of genipin. Besides genipin, Eucommia ulmoides Oliver is abundant in geniposide, and geniposide is a glycoside of genipin and can be biotransformed into genipin through enzymatic biotransformation (Lv et al., 2019). Therefore, a microreactor loaded with enzyme can be constructed for the production of genipin.

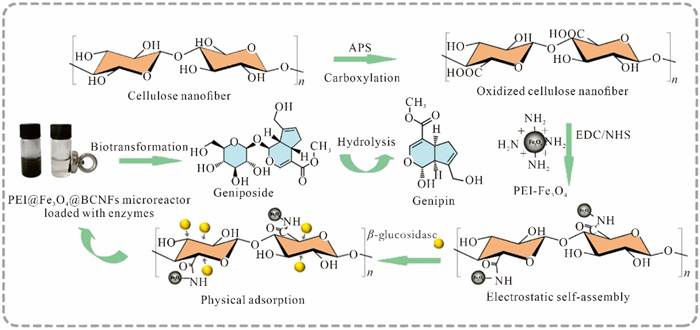

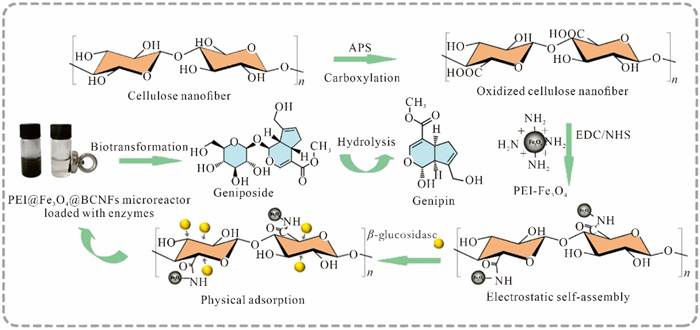

In this study, Fe3O4 nanoparticles modified with polyethylene imine (PEI) form a carrier with cellulose through electrostatic self-assembly, followed by PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs (bamboo-based cellulose nanofibers) carriers interacting with enzymes and ultimately construct a PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs microreactor loaded with the enzyme. The aim of this study is to achieve the transformation of geniposide to genipin by constructing an immobilized β-glucosidase microreactor. The feasibility of this system provides a new technological pathway for the enzymatic transformation research of other phytochemicals.

The β-glucosidase was obtained from Shanghai Yingxin Laboratory. Standard geniposide and genipin were purchased from Vicki Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (China). Sodium citrate, sodium hydroxide, potassium dihydrogen phosphate, sulfuric acid, and sodium carbonate were obtained from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (China). The 4-Nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (pNPG) was acquired from Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (China). Polyethyleneimine was purchased from Heowns Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (China). The Fe3O4, 1-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydro (EDC), 4-Nitrophenol, N—Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), ammonium persulphate (APS), potassium dichromate, hydrochloric acid, potassium iodide (SSKI oral solution) and sodium thiosulfate were obtained from Aladdin Industrial Inc. (China). The 3,5-dinitrosalicylic (DNS) acid was purchased from Leagene. Deionized water was purified by a Milli-Q Water Purification system (Millipore, USA). The Chimonocalamus pallens Hsueh et Yi. was obtained from Pu’er City, Yunnan Province, China, and E. ulmoides Oliver was collected from the campus of Beijing Forestry University.

The dry bamboo power was obtained by Chinese medicine grinding machine. First, 1 g bamboo powder (60 mesh sieve (0.25 mm)) was added into a 50 mL APS solution and reacted it under magnetic stirring at 70 ℃ for 16 h. After the reaction, the obtained APS oxidation pulp was centrifuged and washed until the pH was neutral (Jiang et al., 2017). Oxidized cellulose was obtained after drying the APS oxidation pulp at 45 ℃ in an oven, and was collected as a flocculent powder. Then, the dried oxidized cellulose was dispersed in water (cellulose concentration of 1% (w)), and performed ultrasonic treatment at 500 W for 6 h to obtain uniformly dispersed carboxylated BCNFs. The BCNFs were placed into a beaker and stored under low-temperature condition.

The degradation effect and conductivity of bamboo powder lignin treated with ammonium persulfate oxidation pre-treatment were tested. The Klason method was used to determine the lignin content in bamboo powder (Li et al., 2021). The yield of APS oxidation pulp was calculated by drying the APS oxidation pulp obtained from bamboo powder (m1) of the same quality under different reaction conditions in an oven until constant weight (m2), and the APS oxidation pulp yield (Y) was determined using the following equation (Zhang et al., 2016):

| $$ Y=\frac{m_2}{m_1} \times 100 $$ | (1) |

The carboxyl content on the surface of BCNFs was quantitatively analyzed using conductivity titration technology (Zhang et al., 2022). The steps are as follows: 0.23 g freeze-dried BCNFs were dispersed in a mixture of deionized water (55 mL) and NaCl solution (5 mL, 0.01 mol/L) and stirred for 10 min. After that, 0.1 mol/L HCL was added into the dispersion system to reduce its pH to 3.0, then titrated with 0.01 mol/L NaOH solution (0.1 mL/min) until the pH reaches 10. Finally, the correlation graph between conductivity and the titration amount of NaOH was constructed by calculating the NaOH difference between the start and end of the plateau region, which represents the amount of NaOH needed to neutralize the carboxylic acid group.

Firstly, 1 g Fe3O4 nanoparticles, 0.1588 g sodium citrate, and 5.4 g PEI were mixed at 85 ℃ for 3 h, and the mixture was washed by magnetic separation and dispersed in 10 mL of deionized water by ultrasound to obtain PEI@Fe3O4.

Then, EDC (30 mg) and NHS (15 mg) were added to the BCNFs aqueous suspension and stirred for 30 min. Among them, EDC and NHS were used as carboxyl activators (Je et al., 2017). Subsequently, 10 mL PEI@Fe3O4 solution was added into BCNFs aqueous suspension and ultrasound under ice bath for 2 h, and the PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs was washed thrice with buffer solution. Finally, PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs was freeze-dried and stored for future use.

The process of preparing a microreactor loaded with β-glucosidase is shown in Fig. 1. The 4 mg dry PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs was added into 100 μL of 120 U β-glucosidase and reacted for 4 h at 50 ℃ in a shaker. Finally, the PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs microreactor loaded with β-glucosidase was separated with enzyme solution by magnetic iron and washed with phosphate buffer (pH 5.5).

The Bradford method was employed to determine the immobilization of β-glucosidase (Bradford, 1976). The immobilized enzyme solution and the immobilized scrubbing solution were mixed with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 solution, respectively. After incubating the mixture at 37 ℃ for 30 min, the reaction was evaluated by measuring absorbance at 595 nm.

The materials were freeze-dried with a Freezone 4.5 L lyophilizer. The molecular mass of BCNFs was measured by an ubbelohde viscometer (Liu et al., 2016). Cellulose content was determined by the potassium dichromate iodometric method and the hydrochloric acid hydrolysis method, the hemicellulose content and lignin content were determined by DNS method and classical Klason method, respectively (Li et al., 2021).

The morphological structure of the BCNFs and PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs were observed by scanning electron microscope (SEM, Regulus8100, Tokyo, Japan) and atomic force microscopy (AFM, Bruker Multimode 8, Karlsruhe, Germany). The images captured by AFM were used to determine the dimensions of the BCNFs and PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs. The particle size of BCNFs was measured using Anton Paar Litesizer DLS 500 (Graz, Austria). The chemical structure was tested by a Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrometer (Nicolet 6700, Madison, USA). Spectrophotometric measurements were probed by a P7 Double Beam UV–Visible (UV–vis) spectrophotometer (Shanghai, China). The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area and the total pore volume were measured with a surface area and porosimetry analyzer (Kubo-X1000, Beijing, China). The thermal stability of the samples was tested by a thermogravimetric analyzer (DTG-60, Kyoto, Japan). Solid-state 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy of bamboo powder and BCNFs was tested by an AVANCE IIIHD 500MHz spectrometer (Hong Kong, China). The structural and phase composition changes of the sample were analyzed by X-ray diffractometer (XRD) (D8 Advance, Karlsruhe, Germany), and the crystallinity index (CI, CI in the equation) was calculated using the following equation (Park et al., 2010):

| $$ C_I=\left(I_{200}-I_{a m}\right) / I_{200} \times 100 \% $$ | (2) |

where I200 is the maximum peak intensity at around 2θ = 22.1°; Iam is the minimum peak intensity between the planes (200) and (110).

The pNPG method is used to determine enzyme activity (Norkrans, 1957). The 0.1 mg of β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs was incubated with 0.5 mL of 5 mmol/L pNPG and 0.5 mL phosphate buffer (pH 6) at 50 ℃ for 30 min. After that, Na2CO3 (2 mL, 1 mol/L) was added to the mixture and the absorbance was measured at 400 nm. This process was repeated three times for each sample and the average was taken. The assay-defined activity refers to mmol of p-nitrophenol produced per minute under the specified experimental conditions (U), and U/mg represents the concentration unit of the enzyme. The maximal enzyme activity value is set to 100%, against which the relative activities of each experimental series were assessed and quantified.

The hydrolysis reaction of p-nitrophenol was monitored to ascertain the kinetic properties of both free and immobilized β-glucosidase microreactors. The reaction rates were measured under conditions that had been optimized (0.6 U, 50 ℃, pH 5.5 for free β-glucosidase and 50 ℃, pH 5 for immobilized β-glucosidase). The concentrations of pNPG varied from 7 to 20 mmol/L in phosphate buffer solution. The data were fitted using Michaelis-Menten equation to determine the values of the Michaelis constant (Km), and maximum reaction velocity (Vmax) parameters (Zhang et al., 2020).

The effects of different pH (from 3.5 to 6.0) on the activity of free and immobilized β-glucosidase were studied at 50 ℃. The thermal effects on the activity of free β-glucosidase at pH 5 and immobilized β-glucosidase at pH 5.5 were determined by assaying the enzyme activity from 35 to 60 ℃.

The storage stability of free and immobilized β-glucosidase under 4 ℃ was assessed by regularly calculating their residual activity. During the reusability testing of immobilized β-glucosidase microreactor, the substrate solution was separated from the microreactor using a magnet. The microreactor was then washed with phosphate buffer solution to remove residual substrates after each cycle of enzyme activity measurement. After that, the washed microreactor was added into a new substrate solution to prepare for the next reaction cycle.

The E. ulmoides Oliver roots were powdered, and then 0.1 g of E. ulmoides Oliver roots powder was mixed with 2 mL of deionized water. The mixture was treated with ultrasound at 40 ℃ for 60 min, and the obtained extract was filtered and stored at 4 ℃.

Biotransformation of standard geniposide: β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs (1 mg) or free β-glucosidase (3 U) was added to 50 μL of geniposide solution (250 μg/mL) and adjusted to a specific pH (4.0–8.0). Then the mixture was placed on a shaker for 1–8 h at 20–60 ℃. The solution after incubation was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis, and the entire experimental process was repeated three times to ensure the accuracy of the results.

Biotransformation of E. ulmoides Oliver extracts: 8 mg of PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs immobilized β-glucosidase was add to 2 mL of E. ulmoides Oliver roots extract solution. Then, the mixture was placed on a shaker for 4 h at 40 ℃. After biotransformation, the mixture was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane for HPLC analysis, and the experiment was repeated thrice.

Bamboo cellulose is treated with solid oxidant ammonium persulfate and subjected to ultrasound to obtain oxidized cellulose nanofiber. Further activation of carboxyl groups on nanofiber using EDC and NHS as activators. The β-glucosidase was immobilized onto the as-prepared nanofibers beads through physical adsorption. In addition, the recycling of immobilized enzymes is also achieved through an external magnetic field. After preparing PEI-modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles, they were electrostatically self-assembled onto the nanofiber surface to form magnetic nanofiber, which is insoluble in water and has good stability.

Fig. S1(a) shows the removal rate of lignin under different APS solution concentration conditions. The results show that higher APS concentration is more conducive to lignin degradation, but the yield of APS oxidized pulp gradually decreases. The lignin removal rate is as high as 64.59% when the APS concentration is 2 mol/L, which is because under specific reaction solid-liquid ratio and temperature conditions, the higher the APS concentration, the more oxidized free radicals dissociated and decomposed, and the more severe the degradation of lignin. At the same time, it also degrades cellulose to a certain extent, which leads to a decrease in the yield of cellulose. Fig. S1(b) shows the APS oxidation pulp yield and lignin removal rate at different reaction times. Among them, the yield of APS shows a decreasing trend, significantly a sharp decrease within 0–4 h. This may be due to the infiltration of sulfate and sulfite radicals decomposed by APS into the amorphous region of cellulose and the hydrolysis of cellulose chains in the 1,4-β bond, resulting in a decrease in cellulose. As shown in Figs. S1(c) and (d), the carboxyl content of oxidized BCNFs was determined to be 0.72 mmol/g. The higher the carboxyl content, the more advantageous it will be for the subsequent modification process.

To further optimize the BCNFs preparation conditions and maximize BCNFs yields. As shown in Fig. 2, the optimum process conditions for preparing BCNFs from bamboo powder treated with APS oxidation pre-treatment are ammonium persulfate concentration of 2 mol/L, reaction temperature of 70 ℃, and solid-liquid ratio of 1꞉50, and the final BCNFs yield is 30.08%. Excessive reaction temperature may be unfavorable for the decomposition of APS in aqueous solution, resulting in insufficient oxidative free radicals to decompose lignin into small water-soluble molecules, thereby affecting the yield of BCNFs.

The main chemical components of bamboo are cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Fig. 3a shows that the lignin content of BCNFs decreases significantly, from 28.29% to 10.94%. Meanwhile, the cellulose content increases significantly, reaching 61.66%. This indicates that APS effectively oxidizes and destroys amorphous regions from cellulose, removing lignin and hemicellulose.

The degree of polymerization (DP) and molecular mass of cellulose was determined by viscosity method. The significant decrease in molecular mass of BCNFs indicates that APS can cause severe degradation of cellulose and damage its molecular chains. The molar mass parameters of the original bamboo powder and their BCNFs are listed in Table 1. The DP value of unoxidized bamboo powder is 649, which is consistent with other literature reports. The DP value of bamboo stem material was measured to be 679 (Zhang et al., 2019). After oxidation, the DP value of BCNFs decreases to 496, which may be due to the depolymerization caused by some free radical species formed during the oxidation process (Zhang et al., 2016). As described in the literature, the oxidation treatment of cellulose leaded to a significant decrease in the DP of the raw material (145–997) (Zhang et al., 2016).

| Sample | Molar mass | DP |

| Bamboo powder | 105156 ± 1122.37 | 649 ± 6.93 |

| BCNFs | 80370 ± 1028.84 | 496 ± 6.35 |

| Notes: DP, degree of polymerization; BCNFs, bamboo-based cellulose nanofibers. | ||

The active hydroxyl groups on the cellulose structural unit are located at the C2, C3 and C6 positions (Hou et al., 2024a). The higher active carboxyl groups can be obtained by oxidizing these –OH groups at specific conditions. The solid-state 13C NMR spectroscopy explored the chemical structures of bamboo powder and BCNFs (Fig. 3b). Compared to bamboo powder, the spectrum after APS oxidation showed a decrease in resonance bands around 56.17 × 10–6, 117.01 × 10–6–173.14 × 10–6 and 21.86 × 10–6, and this change is related to the integrity of cellulose crystals. The spectra within the range of 110 and 60 × 10–6 show resonance characteristics of crystalline cellulose (Yang et al., 2015). In Fig. 3b, the peaks of cellulose C1 are around 105 × 10–6, while the peaks of cellulose C4 in the crystalline and amorphous regions are around 88 × 10–6 and 83 × 10–6, respectively. The peak near 63 × 10–6 belongs to cellulose C6. In addition to the characteristic signals mentioned, the complex cluster of peaks between 67 and 80 × 10–6 is attributed to the overlapping contributions from the C2, C3, and C5 carbons (Zhang et al., 2025).

The SEM images of BCNFs before and after APS oxidation treatment and ultrasonic treatment are shown in Fig. 4. Fig. 4a is a SEM image of the raw material of bamboo power, which shows that the bamboo fibers are disordered, and the fiber surface is rough. Fig. 4b is the image of the APS oxidation pulp’s SEM. After the APS oxidation reaction, fiber bundles are separated into independent microscale fibers due to the degradation of lignin on their surface. The fiber surface is relatively pure, and each independent fiber surface has wrinkles and cracks, which provides favorable conditions for subsequent ultrasonic fiber opening. As revealed in Fig. 4c, BCNFs have a diameter of about 30–500 nm and 700–1800 nm in length; the maximum aspect ratio reaches 60, much higher than the cotton and linen fiber (2.51–4.58). The particle size distribution of BCNFs was obtained from the particle size measurement experiment with a center of 396 nm and a standard deviation of 68.32 nm (Fig. S2), within the size range obtained from SEM images. According to the AFM images, Fig. 4d shows the magnetic nanoparticles successfully electrostatic self-assembly with BCNFs to obtain PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs. The size of the magnetic nanoparticles closest to the fiber is 206 nm, and PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs is prone to aggregation due to its magnetic properties. Fig. 4g shows the 3D AFM images of magnetic nanoparticles on BCNFs. Figs. 4e and 4h show the approximate morphology of the enzyme, which has a diameter of around 50 nm and a height of around 4 nm. The AFM image (Fig. 4f) shows the material size obtained is an average length of 1020 nm and an average width of 44.67 nm, Figs. 4f and 4i show the enzyme attached to the PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs (enzyme with a diameter of 79 nm attached to PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs), this observation indicates that the enzyme has been successfully immobilized on the PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs to obtain the microreactor loaded with the enzyme.

The presence of many negative charges on the surface of BCNFs can be measured by zeta potential. In this study, the zeta potential of BCNFs suspension was −1.8 ± 0.05 mV, which was attributed to the presence of carboxyl groups on the surface of the BCNFs. The Zeta potential changes of BCNFs, Fe3O4, and PEI-Fe3O4 within pH 2–10 are shown in Fig. 5a. It can be observed that Fe3O4 exhibits a negative charge at different pH, while PEI-Fe3O4 exhibits a positive charge after PEI surface treatment. This is because PEI is a polymer with a high positive charge density. After surface treatment, Fe3O4 is covalently bonded to PEI molecules, resulting in PEI-Fe3O4 nanoparticles exhibiting high positivity. The nanofiber surface exhibits a negative charge, elucidating the electrostatic self-assembly process on the nanofiber surface.

The FT-IR analysis confirmed the existence of characteristic functional groups of synthetic products. Fig. 5b shows the infrared spectrum of APS oxidation pulse, BCNFs, PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs and β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs. The three spectra all have peaks at 3340 and 2890 cm–1, respectively, belonging to the stretching vibration peak of –OH and the asymmetric stretching vibration peak of CH2 in the cellulose molecular chain, representing the main components in cellulose (Popescu et al., 2009). The absorption peak around 1733 cm–1 is attributed to the C = O stretching vibration on the acetyl and carboxylic acids of hemicellulose in bamboo material. The bamboo material becomes smooth after APS pre-treatment, indicating that hemicellulose has undergone degradation. The results of Fig. 5b also reveals the carboxyl group stretching vibration peak observed at 1610 cm–1 after oxidation treatment, which was introduced by selective oxidation of the C6 primary hydroxyl groups on the glucose ring in the material (Sehaqui et al., 2015). There is a typical absorption band at 1033 cm–1, which corresponds to C–O–C skeletal vibrations of cellulose, demonstrating that PEI achieves effective deposition on oxidized BCNFs through electrostatic self-assembly without damaging the structure of cellulose nanofibers. The β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs spectrum in Fig. 5b shows a broad and flat peak appearing around 3300 cm–1, which is formed by the combination of N–H stretching vibration absorption and O–H absorption peaks of hydrogen bonds between molecules. The vibration peak near 1600 cm–1 is the amide Ⅰ band, and the vibration peak near 1500 cm–1 is the amide Ⅱ band, directly reflecting the protein conformation of β-glucosidase. The electrostatic self-assembly of PEI on the oxidized BCNFs guaranteed the physical adsorption of β-glucosidase on PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs beads. In addition, the UV spectrum shows an absorption peak of β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs around 257 nm, which represents phenylalanine in the enzyme protein and reflects the immobilization of β-glucosidase on PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs (Fig. S3). Subsequent XRD and thermogravimetric characterization were further confirmed.

The XRD analysis was carried out to investigate the basic polycrystalline morphology and changes in the crystal structure of BCNFs. The peak at 15.7° in Fig. 5c corresponds to the (110) and (1–10) crystal planes, and the peaks at 22.1° and 34.7° correspond to the (200) and (004) crystal planes of cellulose, corresponding to the three crystal planes of cellulose (110), (200), and (004), belonging to the typical cellulose Ⅰ structure (Luzi et al., 2019). The change in XRD pattern shows that the peak intensity of oxidized cellulose at 2θ of 22.1° becomes sharper than that of bamboo powder fiber, indicating a significant increase in the crystallinity of the sample. The crystallinity of bamboo powder was calculated to be 44.71%, and the crystallinity of oxidized cellulose was 56.52%. This was attributed to the hydrolysis or substantial removal of the amorphous non-cellulosic components in the bamboo powder during APS oxidation (Adel et al., 2018). In Fig. 5d, both PEI@Fe3O4 and PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs exhibit six characteristic peaks of pure Fe3O4 anti-spinel structure, located at 2θ = 30.2°, 35.7°, 43.1°, 53.4°, 57.1°, 62.7°, corresponding to different crystal planes (220), (311), (400), (422), (511), and (440), respectively. Simultaneously, the figure shows PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs responds to the (200) crystalline plane at 2θ = 22.1°, indicating a crystalline cellulose structure. The XRD pattern indicates that PEI@Fe3O4 has been successfully dispersed on the surface of BCNFs, and the crystal structure has not changed. Moreover, the diffraction intensity of cellulose characteristic peaks significantly decreased, indicating an interaction between BCNFs and PEI@Fe3O4.

Fig. 5e shows a N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm and pore size distribution of PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs. The nitrogen adsorption and desorption curve is the typical type Ⅳ curve. The BET-specific surface area test result is 4.48 m2/g, and the pore-size distribution indicated that both mesopores and micropores were distributed within the diameter range. The specific surface area and pore structure of PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs provide a favorable environment for the subsequent enzyme immobilization.

The thermal stability of bamboo power, BCNFs, oxidized cellulose and PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs was evaluated in the nitrogen by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), as shown in Fig. 5f. In stage Ⅰ, within the temperature range of 100–220 ℃, physically weak and chemically strong bound water molecules were evaporated from the sample. Stage Ⅱ is the rapid cracking stage, occurring between 220 and 370 ℃, with the highest mass loss rate in this range, during which carbohydrates begin to decompose. The third stage occurs between 370 and 650 ℃, during which the quality tends to stabilize. At this stage, the remaining minerals are obtained after high-temperature combustion and ashing. The residual weight of BCNFs at 700 ℃ is about 35% (w), and the residual weight of magnetic nanofiber after pyrolysis at 700 ℃ is as high as 51.4% (w). This result further confirms the combination of PEI@Fe3O4 nanoparticles and BCNFs. The results of Fig. 5f suggest that the initial decomposition temperature of bamboo powder is 180 ℃, and the initial decomposition temperature of PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs is 260 ℃, indicating that PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs have better thermal stability than bamboo materials.

The superiority of immobilized β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs compared with free β-glucosidase has also been analyzed (Fig. 6). The immobilization rate of β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs increased with initial enzyme concentrations ranging from 20 to 120 U/mL. In contrast, the immobilization rate gradually decreases at an initial enzyme concentration of 120–180 U/mL (Fig. 6a). When the initial enzyme concentration is 120 U/mL, the immobilization rate reaches 84.7%. Fig. 6b shows that as the dose of enzyme increases, the enzyme loading on β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs also increases accordingly. Still, the relative activity showed a trend of increasing and then decreasing, which may be due to the occupation of PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs reaction sites by the increase of enzymes, and the immobilization rate of enzyme decreases as the number of unbound enzymes increases.

The pH also has a significant impact on enzyme activity. Fig. 6c shows the relative activity of free enzyme and immobilized β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs was compared at a pH range of 3.5–6.0, indicating that they had a similar but remarkable change trend. As the pH increased from 3.5 to 5.0, the relative activity of the enzyme shows an increasing trend, but when the pH increased from 5.0 to 6.0, the relative activity of immobilized enzymes remained high. In contrast, when the pH value increases from 5.0 to 6.0, the relative activity of immobilized enzyme remains high. Especially at pH 5.5, the relative enzyme activity of β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs was significantly higher than that of free enzyme (99.29% and 90.68%, respectively). This indicates that the acid-base resistance of β-glucosidase has been improved through immobilization treatment. The results of Fig. 6d reveal that under pH 6.0, the temperature between 35 and 60 ℃ significantly affects the relative activity of the free and immobilized enzymes. It can be observed that the two kinds of β-glucosidase exhibit similar trends in their effects. Notably, the free enzyme and the immobilized β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs had the highest relative activity at 50 ℃. And the specific activity of free enzyme and immobilized β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs at 50 ℃ were 0.45 ± 11.07 U/g and 0.37 ± 3.82 U/g, respectively. The enzyme immobilization efficiency of β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs reached its maximum of 82.31% under this condition. Compared with the corresponding free enzyme, the reason for the decrease in specific activity may be due to the enzyme reacting for a long time under high temperature conditions. When the temperature is 35 ℃, the relative activity of free enzyme is only 43.08%, while the relative activity of β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs reaches 71.31%. The enhanced thermal stability of β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs indicates that the microreactor can be applied to enzymatic reactions over a wider temperature range. And when the system temperature was 50–60 ℃, the immobilized β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs performed higher temperature endurance than the free enzyme. The PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs microreactor load β-glucosidase can significantly improve the temperature resistance of β-glucosidase.

The catalysis performance of β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs and the free enzyme was evaluated by using Michaelis-Menten. Table 2 presents the results of Michaelis-Menten, and the Km is a parameter for evaluating the affinity between an enzyme and a specific substrate, the Vmax refers to the maximum reaction velocity of enzymatic reaction. The Km (Michaelis constant) of the immobilized enzyme (42.38 ± 3.91 mmol/L) is higher than that of the free enzyme (12.66 ± 2.37 mmol/L), indicating a lower affinity of immobilization for its substrate. The Vmax (maximum reaction velocity) of immobilized enzyme was remarkably lower than the free enzyme. Kinetic parameters indicated a decrease in the ability of immobilized β-glucosidase to bind to substrates, and the maximum reaction velocity was also lower than the free enzyme. This may be due to the limited accessibility of enzyme active points after immobilization, which is caused by increased steric and diffusion resistance after enzyme immobilization.

| Biocatalyst | Km (mmol/L) | Vmax (μmol/L·min–1) |

| Free enzyme | 12.66 ± 2.37 | 1.52 ± 0.23 |

| Immobilized enzyme | 42.38 ± 3.91 | 1.36 ± 0.09 |

| Notes: Km, Michaelis constant; Vmax, maximum reaction velocity. | ||

Fig. 7a explores the stability of relative activity over time. The relative activity of free enzymes showed a rapid decline from the 6th day, while β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs maintained over 80% of the relative activity at 4 ℃ for an extended period of about 6 d, indicating that immobilization techniques greatly contribute to maintaining enzyme activity. The results showed that even after 15 d of storage, the relative activity stability of immobilized β-glucosidase was better than that of free enzyme. In comparison, the relative activity of the free enzyme had a lower stability and decreased storage time.

A significant advantage of PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs is its reusability. As shown in Fig. 7b, the immobilized enzyme could maintain 76.47% activity after five use cycles. This indicates that the carboxyl groups on the surface of the PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs effectively immobilized β-glucosidase. In addition, this result also points out the BCNFs have potential application value as enzyme immobilization carriers.

There was a significant difference between PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs and free enzyme for the biotransformation time. After immobilization, transforming geniposide into genipin requires a longer time. The results of Fig. S4(a) show that when the biotransformation time reaches 5 h, the biotransformation rate reaches 79.6%. However, for the free enzyme, the biotransformation rate was 79.2% was achieved within 3 h. This difference may be due to the different dispersibility of immobilized and free enzymes in the solution. The free enzyme has better dispersibility in the reaction solution than the immobilized enzyme. Hence, this increases the contact rate between free enzymes and substrates, which may increase the reaction rate. The Vmax result of free enzyme in the research of kinetic parameters also showed a high level.

There was a similar trend in the biotransformation rate for pH and temperature by both PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs and free enzyme, as shown in Figs. S4(b) and S4(c). When the temperature was 40 ℃, the biotransformation rate was high, however, when the temperature was higher than 50 ℃, the biotransformation rate decreased. When the pH was 5, the biotransformation rate was 93.10%, but as the pH value continued to increase, the biotransformation rates decreased sharply. Overall, PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs and free enzymes showed similar trends in the experiment, indicating that the PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs, as carriers of β-glucosidase, which did not markedly alter the properties and structure of the enzyme and affect the catalytic properties of β-glucosidase.

The PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs were used in the biotransformation of E. ulmoides Oliver extracts. As shown in Fig. 8, before transformation, the concentrations of geniposide and genipin were calculated based on the standard curve to be 41.94 ± 2.64 μg/mL and 73.64 ± 7.5 μg/mL, respectively. The concentration of geniposide decreased to 3.65 ± 0.43 μg/mL and the concentration of genipin increased to 93.63 ± 8.43 μg/mL after transformation (Fig. 8). The transformation rate of geniposide reached 93.10%, and the genipin concentration increased 1.2 folds higher than the original E. ulmoides Oliver extracts. It means the PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs can be successfully used in the transformation of geniposide.

To evaluate the transformation rate of PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs, different methods for biotransforming geniposide to genipin were compared (Table 3). Immobilized on the sodium alginate β-glucosidase efficiently produces genipin, and the hydrolysis yield could reach 47.81%, which is lower than this experiment (Yang et al., 2011). Some studies have also used microbial transformation methods to biotransform geniposide into genipin, while making the separation process more difficult and requiring a longer time (Xu et al., 2008; Dong et al., 2014). Thus, magnetic nanofiber immobilized β-glucosidase, as an efficient biobased carrier, has the advantages of a high substrate transformation rate and short transformation time and has potential application value in the study of the biotransformation of geniposide to genipin. Moreover, in the HPLC chromatogram, there is a significant peak decrease at 5 min after biotransformation, indicating that geniposidic acid may be oxidized in the presence of Fe3+ or reactive oxygen species due to the presence of phenolic hydroxyl groups (Ahmad and Bensalah, 2022).

| Method | Time (h) | Conversion rate of genipin (%) | References |

| The crosslinking-embedding method using sodium alginate as the carrier | 2.5 | 47.81 | Yang et al., 2011 |

| A filamentous fungi strain, Penicillium nigricans, producing β-glucosidase was screened to transform geniposide | 72 | 95 | Xu et al., 2008 |

| Lactic acid bacteria | 12 | 93.4 | Li et al., 2023 |

| β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs | 4 | 93.1 | This work |

| Note: PEI, polyethylene imine. | |||

Bamboo biomass has a low cost of approximately 100 dollar (USA) per metric ton. Globally, the area of bamboo forests exceeds 36 million hectares, accounting for nearly 0.92% of the world’s total forest area (Zhan et al., 2024). Carbon based carrier materials such as carbon nanotubes have expensive costs (303–455 dollar (USA) per metric ton) due to their complex synthesis process and high purity required for applications, as well as potential toxicity due to their aggregation behavior and the presence of residual metal pollutants during the synthesis process (Liu et al., 2023). However, the preparation process of bamboo fiber is simple and requires low equipment, the application of bamboo fiber carrier saves costs in the preparation process.

In this study, the magnetic nanofiber microreactor loaded with enzymes was successfully prepared with an immobilization rate of 84.7%. The immobilized β-glucosidase on PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs microreactor possessed good catalytic activity. It can be used for the biotransformation of geniposide to genipin in E. ulmoides Oliver extracts. The transformation rate of geniposide reached 93.10%, and after biotransformation, the genipin concentration increased 1.2 folds higher than that in the original extracts. Moreover, the PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs microreactor had good reusability, and could maintain 76.47% activity after five runs. In conclusion, the magnetic nanofiber microreactor shows excellent catalytic activity for transforming geniposide into genipin, and it may also be used to transform other plant phytochemicals in the natural production field. Therefore, magnetic nanofiber microreactors loaded with enzymes have promising prospects in biotransformation for phytochemicals.

Acknowledgments: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32271805), National Science and Technology Innovation Project (No. 2022XACX1100), National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFD2200602), the 111 Center (No. B20088) and 5·5 Engineering Research & Innovation Team Project of Beijing Forestry University (No. BLRC2023A01).|

Adel, A., El-Shafei, A., Ibrahim, A., Al-Shemy, M., 2018. Extraction of oxidized nanocellulose from date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) sheath fibers: Influence of CI and CII polymorphs on the properties of chitosan/bionanocomposite films. Ind. Crops Prod. 124, 155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.07.073

|

|

Ahmad, M.I., Bensalah, N., 2022. Insights into the generation of hydroxyl radicals from H2O2 decomposition by the combination of Fe2+ and chloranilic acid. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19, 10119–10130. doi: 10.1007/s13762-021-03822-0

|

|

Ariaeenejad, S., Hosseini, E., Motamedi, E., Moosavi-Movahedi, A.A., Salekdeh, G.H., 2019. Application of carboxymethyl cellulose-g-poly(acrylic acid-co-acrylamide) hydrogel sponges for improvement of efficiency, reusability and thermal stability of a recombinant xylanase. Chem. Eng. J. 375, 122022. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2019.122022

|

|

Ariaeenejad, S., Motamedi, E., Hosseini Salekdeh, G., 2021. Immobilization of enzyme cocktails on dopamine functionalized magnetic cellulose nanocrystals to enhance sugar bioconversion: A biomass reusing loop. Carbohydr. Polym. 256, 117511. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117511

|

|

Balakrishnan, A., Jacob, M.M., Chinthala, M., Dayanandan, N., Ponnuswamy, M., Vo, D.N., 2024. Photocatalytic sponges for wastewater treatment, carbon dioxide reduction, and hydrogen production: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 22, 635–656. doi: 10.1007/s10311-024-01696-5

|

|

Banjanac, K., Carević, M., Ćorović, M., Milivojević, A., Prlainović, N., Marinković, A., Bezbradica, D., 2016. Novel β-galactosidase nanobiocatalyst systems for application in the synthesis of bioactive galactosides. RSC Adv. 6, 97216–97225. doi: 10.1039/C6RA20409K

|

|

Bradford, M.M., 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3

|

|

Chen, C.J., Kuang, Y.D., Zhu, S.Z., Burgert, I., Keplinger, T., Gong, A., Li, T., Berglund, L., Eichhorn, S.J., Hu, L.B., 2020. Structure–property–function relationships of natural and engineered wood. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 642–666. doi: 10.1038/s41578-020-0195-z

|

|

Chen, Z.Y., Xie, Z.Y., Jiang, H., 2023. Extraction of the cellulose nanocrystals via ammonium persulfate oxidation of beaten cellulose fibers. Carbohydr. Polym. 318, 121129. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.121129

|

|

Devireddy, S.B.R., Biswas, S., 2016. Physical and thermal properties of unidirectional banana–jute hybrid fiber-reinforced epoxy composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 35, 1157–1172. doi: 10.1177/0731684416642877

|

|

Dong, Y.S., Liu, L.P., Bao, Y.M., Hao, A.Y., Qin, Y., Wen, Z.J., Xiu, Z.L., 2014. Biotransformation of geniposide in Gardenia jasminoides to genipin by Trichoderma harzianum CGMCC 2979. Chin. J. Catal. 35, 1534–1546. doi: 10.1016/S1872-2067(14)60134-0

|

|

Du, Y.C., Feng, G.F., 2023. When nanocellulose meets hydrogels: The exciting story of nanocellulose hydrogels taking flight. Green Chem 25, 8349–8384. doi: 10.1039/d3gc01829f

|

|

Gennari, A., Führ, A.J., Volpato, G., Volken de Souza, C.F., 2020. Magnetic cellulose: Versatile support for enzyme immobilization—A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 246, 116646. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116646

|

|

Gkantzou, E., Chatzikonstantinou, A.V., Fotiadou, R., Giannakopoulou, A., Patila, M., Stamatis, H., 2021. Trends in the development of innovative nanobiocatalysts and their application in biocatalytic transformations. Biotechnol. Adv. 51, 107738. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2021.107738

|

|

Guo, K.N., Zhang, C., Xu, L.H., Sun, S.C., Wen, J.L., Yuan, T.Q., 2022. Efficient fractionation of bamboo residue by autohydrolysis and deep eutectic solvents pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 354, 127225. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127225

|

|

Hosseini, S.H., Hosseini, S.A., Zohreh, N., Yaghoubi, M., Pourjavadi, A., 2018. Covalent immobilization of cellulase using magnetic poly(ionic liquid) support: improvement of the enzyme activity and stability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 789–798. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b03922

|

|

Hou, G.Y., Chitbanyong, K., Shibata, I., Takeuchi, M., Isogai, A., 2024a. Structural analyses of supernatant fractions in TEMPO-oxidized pulp/water reaction mixtures separated by centrifugation and dialysis. Carbohydr. Polym. 336, 122103. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122103

|

|

Hou, H.Q., Xu, F.R., Ding, X.X., Zheng, L., Shi, J., 2024b. Magnetic biocatalytic nanoreactors based on graphene oxide with graded reduction degrees for the enzymatic synthesis of phytosterol esters. Carbon N Y 226, 119170. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2024.119170

|

|

Jatti, K., Vaishnav, P., Titiksh, A., 2016. Evaluating the performance of hybrid fiber reinforced concrete dosed with polyvinyl alcohol. Int. J. Trend Res. Developm. 3, 354–357.

|

|

Je, H.H., Noh, S., Hong, S.G., Ju, Y., Kim, J., Hwang, D.S., 2017. Cellulose nanofibers for magnetically-separable and highly loaded enzyme immobilization. Chem. Eng. J. 323, 425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.04.110

|

|

Jiang, H., Wu, Y., Han, B.B., Zhang, Y., 2017. Effect of oxidation time on the properties of cellulose nanocrystals from hybrid poplar residues using the ammonium persulfate. Carbohydr. Polym. 174, 291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.06.080

|

|

Jiang, Q.S., Li, Y.J., Wang, M.M., Cao, W., Yang, X.Y., Zhang, S.H., Guo, L.J., 2024. In-situ honeycomb spheres for enhanced enzyme immobilization and stability. Chem. Eng. J. 495, 153583. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2024.153583

|

|

Khanjanzadeh, H., Park, B.D., 2021. Optimum oxidation for direct and efficient extraction of carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals from recycled MDF fibers by ammonium persulfate. Carbohydr. Polym. 251, 117029. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117029

|

|

Li, L.L., Guo, Y.P., Zhao, L.F., Zu, Y.G., Gu, H.Y., Yang, L., 2015. Enzymatic hydrolysis and simultaneous extraction for preparation of genipin from bark of Eucommia ulmoides after ultrasound, microwave pretreatment. Molecules 20, 18717–18731. doi: 10.3390/molecules201018717

|

|

Li, L., Zhou, L., Song, G.S., Wang, D.L., Xiao, G.N., Zheng, F.P., Gong, J.Y., 2023. High efficiency biosynthesis of Gardenia blue and red pigment by lactic acid bacteria: A great potential for natural color pigments. Food Chem 417, 135868. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.135868

|

|

Li, Z.H., Chen, C.J., Xie, H., Yao, Y., Zhang, X., Brozena, A., Li, J.G., Ding, Y., Zhao, X.P., Hong, M., Qiao, H.Y., Smith, L.M., Pan, X.J., Briber, R., Shi, S.Q., Hu, L.B., 2021. Sustainable high-strength macrofibres extracted from natural bamboo. Nat. Sustain. 5, 235–244. doi: 10.1038/s41893-021-00831-2

|

|

Li, Q.H., Yu, D.D., Peng, J., Zhang, W., Huang, J.L., Liang, Z.X., Wang, J.L., Lin, Z.Y., Xiong, S.Y., Wang, J.Z., Huang, S.M., 2024. Efficient polytelluride anchoring for ultralong-life potassium storage: Combined physical barrier and chemisorption in nanogrid-in-nanofiber. Nano-Micro Lett 16, 77. doi: 10.1007/s40820-023-01318-9

|

|

Lin, K., Xia, A., Huang, Y., Zhu, X.Q., Cai, K.Y., Wei, Z.D., Liao, Q., 2022. Efficient production of sugar via continuous enzymatic hydrolysis in a microreactor loaded with cellulase. Chem. Eng. J. 445, 136633. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2022.136633

|

|

Lin, K., Xia, A., Huang, Y., Zhu, X.Q., Zhu, X., Cai, K.Y., Wei, Z.D., Liao, Q., 2023. How can vanillin improve the performance of lignocellulosic biomass conversion in an immobilized laccase microreactor system? Bioresour. Technol. 374, 128775. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2023.128775

|

|

Liu, J.J., Zhang, J.M., Zhang, B.Q., Zhang, X.Y., Xu, L.L., Zhang, J., He, J.S., Liu, C.Y., 2016. Determination of intrinsic viscosity-molecular weight relationship for cellulose in BmimAc/DMSO solutions. Cellulose 23, 2341–2348. doi: 10.1007/s10570-016-0967-1

|

|

Liu, Q., Li, Y., Xing, S., Wang, L., Yang, X.D., Hao, F., Liu, M.X., 2022. Genipin-crosslinked amphiphilic chitosan films for the preservation of strawberry. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 213, 804–813. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.06.037

|

|

Liu, K.M., Song, W.L., Cui, C.J., Jiao, R.J., Yu, X., Wang, J., Li, K., Qian, W.Z., 2023. Process simulation of diesel into aromatics and carbon nanotubes: A techno and economic analyses. ACS Omega 8, 17941–17947. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.3c01135

|

|

Luzi, F., Puglia, D., Sarasini, F., Tirillò, J., Maffei, G., Zuorro, A., Lavecchia, R., Kenny, J.M., Torre, L., 2019. Valorization and extraction of cellulose nanocrystals from North African grass: Ampelodesmos mauritanicus (Diss). Carbohydr. Polym. 209, 328–337. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.01.048

|

|

Lv, J.J., Wang, Y.F., Zhang, C.Y., You, S.P., Qi, W., Su, R.X., He, Z.M., 2019. Highly efficient production of FAMEs and β-farnesene from a two-stage biotransformation of waste cooking oils. Energy Convers. Manag. 199, 112001. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2019.112001

|

|

Mai, X.M., Mai, J.P., Liu, H.J., Liu, Z.J., Wang, R.J., Wang, N., Li, X., Zhong, J., Deng, Q.J., Zhang, H.Q., 2022. Advanced bamboo composite materials with high-efficiency and long-term anti-microbial fouling performance. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 864–871. doi: 10.1007/s42114-021-00380-4

|

|

Meng, S.X., Xue, L.H., Xie, C.Y., Bai, R.X., Yang, X., Qiu, Z.P., Guo, T., Wang, Y.L., Meng, T., 2018. Enhanced enzymatic reaction by aqueous two-phase systems using parallel-laminar flow in a double Y-branched microfluidic device. Chem. Eng. J. 335, 392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.10.085

|

|

Misnon, M.I., Islam, M.M., Epaarachchi, J.A., Lau, K.T., 2014. Potentiality of utilising natural textile materials for engineering composites applications. Mater. Des. 59, 359–368. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2014.03.022

|

|

Norkrans, B., 1957. Studies of β-glucoside- and cellulose splitting enzymes from Polyporus annosus Fr. Physiol. Plant. 10, 198–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1957.tb07621.x

|

|

Park, S., Baker, J.O., Himmel, M.E., Parilla, P.A., Johnson, D.K., 2010. Cellulose crystallinity index: measurement techniques and their impact on interpreting cellulase performance. Biotechnol. Biofuels 3, 10. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-3-10

|

|

Popescu, C.M., Singurel, G., Popescu, M.C., Vasile, C., Argyropoulos, D.S., Willför, S., 2009. Vibrational spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction methods to establish the differences between hardwood and softwood. Carbohydr. Polym. 77, 851–857. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2009.03.011

|

|

Prabhakar, T., Giaretta, J., Zulli, R., Rath, R.J., Farajikhah, S., Talebian, S., Dehghani, F., 2025. Covalent immobilization: A review from an enzyme perspective. Chem. Eng. J. 503, 158054. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2024.158054

|

|

Prakash, C., Ramakrishnan, G., 2014. Study of thermal properties of bamboo/cotton blended single jersey knitted fabrics. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 39, 2289–2294. doi: 10.1007/s13369-013-0758-z

|

|

Saito, T., Kimura, S., Nishiyama, Y., Isogai, A., 2007. Cellulose nanofibers prepared by TEMPO-mediated oxidation of native cellulose. Biomacromolecules 8, 2485–2491. doi: 10.1021/bm0703970

|

|

Sathishkumar, P., Kamala-Kannan, S., Cho, M., Kim, J.S., Hadibarata, T., Salim, M.R., Oh, B.T., 2014. Laccase immobilization on cellulose nanofiber: The catalytic efficiency and recyclic application for simulated dye effluent treatment. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 100, 111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2013.12.008

|

|

Sehaqui, H., Gálvez, M.E., Becatinni, V., Ng, Y., Steinfeld, A., Zimmermann, T., Tingaut, P., 2015. Fast and reversible direct CO2 capture from air onto all-polymer nanofibrillated cellulose-polyethylenimine foams. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 3167–3174. doi: 10.1021/es504396v

|

|

Sirviö, J.A., Ukkola, J., Liimatainen, H., 2019. Direct sulfation of cellulose fibers using a reactive deep eutectic solvent to produce highly charged cellulose nanofibers. Cellulose 26, 2303–2316. doi: 10.1007/s10570-019-02257-8

|

|

Thakur, V.K., Thakur, M.K., Gupta, R.K., 2014. Review: Raw natural fiber-based polymer composites. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 19, 256–271. doi: 10.1080/1023666X.2014.880016

|

|

Tripathi, M., Sharma, M., Bala, S., Connell, J., Newbold, J.R., Rees, R.M., Aminabhavi, T.M., Thakur, V.K., Gupta, V.K., 2023. Conversion technologies for valorization of hemp lignocellulosic biomass for potential biorefinery applications. Sep. Purif. Technol. 320, 124018. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2023.124018

|

|

Tušek, A.J., Tišma, M., Bregović, V., Ptičar, A., Kurtanjek, Ž., Zelić, B., 2013. Enhancement of phenolic compounds oxidation using laccase from Trametes versicolor in a microreactor. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 18, 686–696. doi: 10.1007/s12257-012-0688-8

|

|

Wang, X.Q., Keplinger, T., Gierlinger, N., Burgert, I., 2014. Plant material features responsible for bamboo’s excellent mechanical performance: A comparison of tensile properties of bamboo and spruce at the tissue, fibre and cell wall levels. Ann. Bot. 114, 1627–1635. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcu180

|

|

Wang, B., Wang, J.M., Hu, Z.H., Zhu, A.L., Shen, X.J., Cao, X.F., Wen, J.L., Yuan, T.Q., 2024. Harnessing renewable lignocellulosic potential for sustainable wastewater purification. Research 7, 347. doi: 10.34133/research.0347

|

|

Xu, M.M., Sun, Q., Su, J., Wang, J.F., Xu, C., Zhang, T., Sun, Q.L., 2008. Microbial transformation of geniposide in Gardenia jasminoides Ellis into genipin by Penicillium nigricans. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 42, 440–444. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2008.01.003

|

|

Xu, H.Y., Sanchez-Salvador, J.L., Blanco, A., Balea, A., Negro, C., 2023. Recycling of TEMPO-mediated oxidation medium and its effect on nanocellulose properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 319, 121168. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.121168

|

|

Xu, R., Chen, J.W., Yan, N.N., Xu, B.Q., Lou, Z.C., Xu, L., 2025. High-value utilization of agricultural residues based on component characteristics: Potentiality and challenges. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. doi: 10.1016/j.jobab.2025.01.002.

|

|

Yan, L.B., Chouw, N., Jayaraman, K., 2014. Flax fibre and its composites: A review. Compos. Part B Eng. 56, 296–317. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.08.014

|

|

Yang, Y.S., Zhang, T., Yu, S.C., Ding, Y., Zhang, L.Y., Qiu, C., Jin, D., 2011. Transformation of geniposide into genipin by immobilized β-glucosidase in a two-phase aqueous-organic system. Molecules 16, 4295–4304. doi: 10.3390/molecules16054295

|

|

Yang, H., Chen, D.Z., van de Ven, T.G.M., 2015. Preparation and characterization of sterically stabilized nanocrystalline cellulose obtained by periodate oxidation of cellulose fibers. Cellulose 22, 1743–1752. doi: 10.1007/s10570-015-0584-4

|

|

Zeng, Q.H., Li, H.R., Zhu, Y.Y., Zhou, J.J., Zhu, J.J., Xu, Y., 2024. Efficient co-production of glucose and carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals from cellulose-rich biomass waste residues via low enzymatic pre-hydrolysis and persulfate oxidation. Ind. Crops Prod. 220, 119279. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.119279

|

|

Zhan, B.X., Zhang, L., Deng, Y.Q., Fan, M.H., Yan, L.F., 2024. Sustainable adhesives for ultra-composites from biomass powder. Chem. Eng. J. 485, 149984. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2024.149984

|

|

Zhang, K.T., Sun, P.P., Liu, H., Shang, S.B., Song, J., Wang, D., 2016. Extraction and comparison of carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals from bleached sugarcane bagasse pulp using two different oxidation methods. Carbohydr. Polym. 138, 237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.11.038

|

|

Zhang, W.B., Fei, B.H., Polle, A., Euring, D., Tian, G.L., Yue, X.H., Chang, Y.T., Jiang, Z.H., Hu, T., 2019. Crystal and thermal response of cellulose isolation from bamboo by two different chemical treatments. Bioresources 14, 3471–3480. doi: 10.15376/biores.14.2.3471-3480

|

|

Zhang, D.Y., Wan, Y., Yao, X.H., Chen, C., Ju, Y.X., Shuang, F.F., Fu, Y.J., Chen, T., Zhao, W.G., Liu, L., Li, L., 2020. Fabrication of three-dimensional porous cellulose microsphere bioreactor for biotransformation of polydatin to resveratrol from Polygonum cuspidatum Siebold & Zucc. Ind. Crops Prod. 144, 112029. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.112029

|

|

Zhang, S.D., Lin, Q.Q., Wang, X.Y., Yu, Y.L., Yu, W.J., Huang, Y.X., 2022. Bamboo cellulose fibers prepared by different drying methods: Structure-property relationships. Carbohydr. Polym. 296, 119926. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119926

|

|

Zheng, D., Zheng, Y.L., Tan, J.J., Zhang, Z.J., Huang, H., Chen, Y., 2024. Co-immobilization of whole cells and enzymes by covalent organic framework for biocatalysis process intensification. Nat. Commun. 15, 5510. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-49831-8

|

|

Zhang, Q.Y., Yan, R.J., Xiong, Y.Y., Lei, H., Du, G.B., Pizzi, A., Puangsin, B., Xi, X.D., 2025. Preparation and characterization of polymeric cellulose wood adhesive with excellent bonding properties and water resistance. Carbohydr. Polym. 347, 122705. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122705

|

| [1] | Zhiqiang Fu, Tong Zhao, Hu Wang, Jingyi Wei, Haozhe Liu, Liying Duan, Yan Wang, Ruixiang Yan. Study on the mechanism and law of temperature, humidity and moisture content on the mechanical properties of molded fiber products[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2024, 9(3): 351-368. doi: 10.1016/j.jobab.2024.04.003 |

| [2] | Ryen M. Frazier, Mariana Lendewig, Ramon E. Vera, Keren A. Vivas, Naycari Forfora, Ivana Azuaje, Autumn Reynolds, Richard Venditti, Joel J. Pawlak, Ericka Ford, Ronalds Gonzalez. Textiles from non-wood feedstocks: Challenges and opportunities of current and emerging fiber spinning technologies[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2024, 9(4): 410-432. doi: 10.1016/j.jobab.2024.07.002 |

| [3] | Changjie Chen, Pengfei Xu, Xinhou Wang. Structure and mechanical properties of windmill palm fiber with different delignification treatments[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2024, 9(1): 102-112. doi: 10.1016/j.jobab.2023.12.001 |

| [4] | Korbinian Sinzinger, Ulrike Obst, Samed Güner, Manuel Döring, Magdalena Haslbeck, Doris Schieder, Volker Sieber. The Pichia pastoris enzyme production platform: From combinatorial library screening to bench-top fermentation on residual cyanobacterial biomass[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2024, 9(1): 43-57. doi: 10.1016/j.jobab.2023.12.005 |

| [5] | Yanling Zhang, Chao Duan, Swetha Kumari Bokka, Zhibin He, Yonghao Ni. Molded fiber and pulp products as green and sustainable alternatives to plastics: A mini review[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2022, 7(1): 14-25. doi: 10.1016/j.jobab.2021.10.003 |

| [6] | Xiaoya Jiang, Yuanyuan Bai, Xuefeng Chen, Wen Liu. A review on raw materials, commercial production and properties of lyocell fiber[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2020, 5(1): 16-25. doi: 10.1016/j.jobab.2020.03.002 |

| [7] | Yan Ma, Weihong Tan, Jingxin Wang, Junming Xu, Kui Wang, Jianchun Jiang. Liquefaction of Bamboo Biomass and the Production of Three Fractions Containing Aromatic Compounds[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2020, 5(2): 114-123. doi: 10.1016/j.jobab.2020.04.005 |

| [8] | Chinomso M. EWULONU, Xuran LIU, Min WU, Huang YONG. Lignin-Containing Cellulose Nanomaterials: A Promising New Nanomaterial for Numerous Applications[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2019, 4(1): 3-10. doi: 10.21967/jbb.v4i1.186 |

| [9] | Jiulong XIE, Jinqiu QI, Hongling HU, Cornelis F DE HOOP, Hui XIAO, Yuzhu CHEN, Chungyun HSE. Effect of Fertilization on Anatomical and Physical-mechanical Properties of Neosinocalamus Affinis Bamboo[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2019, 4(1): 67-72. doi: 10.21967/jbb.v4i1.183 |

| [10] | Qiheng TANG, Lu FANG, Wenjing GUO. Effects of Bamboo Fiber Length and Loading on Mechanical, Thermal and Pulverization Properties of Phenolic Foam Composites[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2019, 4(1): 51-59. doi: 10.21967/jbb.v4i1.184 |

| [11] | Xue Song, Mingqin Lin, Changsheng Song, Zipei Shi, Heng Zhang. Pickering emulsion polymerization of styrene stabilized by nanocrystalline cellulose[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2018, 3(4): 134-138. doi: 10.21967/jbb.v3i4.92 |

| [12] | Man Li, Guigan Fang, Zhaosheng Cai, Long Liang, Jing Zhou, Lulu Wei. Combination of ultrasonication/mechanical refining with alkali treatment to improve the accessibility and porosity of bamboo cellulose fibers for the preparation of magnetic bionanocomposite cellulose beads[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2018, 3(2): 40-48. doi: 10.21967/jbb.v3i2.159 |

| [13] | Tian He, Mingyou Liu. Recovery of calcium carbonate waste as paper filler in the causticizing process of bamboo kraft pulping[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2017, 2(2): 82-88. doi: 10.21967/jbb.v2i2.147 |

| [14] | Jun Xu, Guoqiang Zhou, Jun Li, Li-huan Mo. Effects of steam explosion pretreatment on the chemical composition and fiber characteristics of cornstalks[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2017, 2(4): 153-157. doi: 10.21967/jbb.v2i4.100 |

| [15] | Hunan Liang, Xiao Hu. A quick review of the applications of nano crystalline cellulose in wastewater treatment[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2016, 1(4): 207-212. doi: 10.21967/jbb.v1i4.65 |

| [16] | Wenhang Wang, Yabin Wang, Yanan Wang, Xiaowei Zhang, Xiao Wang, Guixian Gao. Fabrication and characterization of microfibrillated cellulose and collagen composite films[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2016, 1(4): 162-168. doi: 10.21967/jbb.v1i4.54 |

| [17] | Zhijun Hu, Jiang Lin, Jessica Wu. Numerical simulation of the motion of cellulose fibers in a centrifugal cleaner[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2016, 1(3): 120-126. doi: 10.21967/jbb.v1i3.23 |

| [18] | Zhiguo Wang, Hui Li, Liang Liu, Jie Jiang, Ke Zheng, Helen Ocampo, Yimin Fan. Stability of partially deacetylated chitin nano-fiber dispersions mediated by protonic acids[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2016, 1(3): 132-138. doi: 10.21967/jbb.v1i3.47 |

| [19] | Zhen Tang, Jie Zheng, Ying Han, Guangwei Sun, Shuo Hu, Yifu Wang, Jinghui Zhou. Adsorption characteristics of surfactants on secondary wood fiber surface[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2016, 1(2): 64-73. doi: 10.21967/jbb.v1i2.31 |

| [20] | Xin Zheng, Xiaojuan Ma, Lihui Chen, Liulian Huang, Shilin Cao, Joseph Nasrallah. Lignin extraction and recovery in hydrothermal pretreatment of bamboo[J]. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, 2016, 1(3): 145-151. doi: 10.21967/jbb.v1i3.50 |

| Sample | Molar mass | DP |

| Bamboo powder | 105156 ± 1122.37 | 649 ± 6.93 |

| BCNFs | 80370 ± 1028.84 | 496 ± 6.35 |

| Notes: DP, degree of polymerization; BCNFs, bamboo-based cellulose nanofibers. | ||

| Biocatalyst | Km (mmol/L) | Vmax (μmol/L·min–1) |

| Free enzyme | 12.66 ± 2.37 | 1.52 ± 0.23 |

| Immobilized enzyme | 42.38 ± 3.91 | 1.36 ± 0.09 |

| Notes: Km, Michaelis constant; Vmax, maximum reaction velocity. | ||

| Method | Time (h) | Conversion rate of genipin (%) | References |

| The crosslinking-embedding method using sodium alginate as the carrier | 2.5 | 47.81 | Yang et al., 2011 |

| A filamentous fungi strain, Penicillium nigricans, producing β-glucosidase was screened to transform geniposide | 72 | 95 | Xu et al., 2008 |

| Lactic acid bacteria | 12 | 93.4 | Li et al., 2023 |

| β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs | 4 | 93.1 | This work |

| Note: PEI, polyethylene imine. | |||

| Sample | Molar mass | DP |

| Bamboo powder | 105156 ± 1122.37 | 649 ± 6.93 |

| BCNFs | 80370 ± 1028.84 | 496 ± 6.35 |

| Notes: DP, degree of polymerization; BCNFs, bamboo-based cellulose nanofibers. | ||

| Biocatalyst | Km (mmol/L) | Vmax (μmol/L·min–1) |

| Free enzyme | 12.66 ± 2.37 | 1.52 ± 0.23 |

| Immobilized enzyme | 42.38 ± 3.91 | 1.36 ± 0.09 |

| Notes: Km, Michaelis constant; Vmax, maximum reaction velocity. | ||

| Method | Time (h) | Conversion rate of genipin (%) | References |

| The crosslinking-embedding method using sodium alginate as the carrier | 2.5 | 47.81 | Yang et al., 2011 |

| A filamentous fungi strain, Penicillium nigricans, producing β-glucosidase was screened to transform geniposide | 72 | 95 | Xu et al., 2008 |

| Lactic acid bacteria | 12 | 93.4 | Li et al., 2023 |

| β-glucosidase/PEI@Fe3O4@BCNFs | 4 | 93.1 | This work |

| Note: PEI, polyethylene imine. | |||